By 1952, instability had already taken root in Richard Speck’s life. That year, his older brother Robert died at the age of 23 in an automobile accident, further fracturing an already volatile family structure. Loss, upheaval, and emotional neglect would become recurring themes in Speck’s formative years.

Between 1951 and 1960, while living in Dallas, Speck developed a reputation as a neighborhood troublemaker. After moving in with his mother, stepfather, and sister, his behavior steadily deteriorated. The family relocated frequently—nearly ten times over a twelve-year span—often settling in impoverished neighborhoods. This constant instability deprived Speck of routine, security, and any lasting sense of belonging.

His relationship with his stepfather proved especially damaging. Speck reportedly despised him, describing a man who was abusive, cold, and frequently absent. The home environment fostered resentment and emotional detachment that would follow Speck into adulthood.

Academically, Speck struggled significantly. He refused to wear his reading glasses, impairing his ability to learn, and ultimately repeated the eighth grade at J. L. Long Junior High School. His difficulties were compounded by intense anxiety—particularly a fear of speaking in class and being stared at by peers—further reinforcing withdrawal and academic failure.

Escalation: 1961–1966

Between 1960 and 1966, Richard Speck cycled relentlessly through jobs, arrests, short sentences, and early releases—each encounter with the criminal justice system ending not in reform, but in escalation.

From 1960 to 1963, Speck worked intermittently as a laborer for a 7-Up bottling company in Dallas. In October 1961, he met 15-year-old Shirley Ann Malone at the Texas State Fair. She became pregnant within weeks. The two married in January 1962 and had a child later that year. The marriage was violent and unstable. Speck raped his wife, reinforcing a pattern of domination and sexual violence that would later define his crimes.

In 1963, Speck was convicted of forgery and burglary after cashing a coworker’s paycheck and robbing a grocery store. He received a three-year prison sentence but was paroled after just sixteen months. His release lasted only a week before another arrest.

In January 1965, Speck attacked a woman in the parking lot of her apartment building while wielding a 17-inch carving knife. He fled when she screamed but was apprehended nearby. Convicted of aggravated assault, he was again sentenced—and again released early due to administrative error. Another opportunity for meaningful intervention was missed.

By late 1965, Speck’s violence had become increasingly public and brazen. In December, while frequenting Ginny’s Lounge in Dallas, he stabbed a man during a knife fight. Though initially charged with aggravated assault, the charge was reduced to disturbing the peace. Speck served three days in jail, marking the last time Dallas police would hold him.

March–April 1966: A Pattern Comes Into Focus

In March 1966, Speck robbed a grocery store, stealing cartons of cigarettes and selling them from the trunk of his car. A warrant for his arrest was issued on March 8. Had it been served, it would have been his forty-second arrest and almost certainly resulted in another prison term.

Instead, on March 9, 1966, Richard Speck boarded a bus to Chicago.

Within weeks, between March and April 1966, Speck raped and robbed Virgil Harris, a 65-year-old woman, stealing money from her. The crime demonstrated his growing boldness and his willingness to target older, vulnerable victims.

Approximately one week later, another woman disappeared.

Mary Kathryn Price, 32, worked at her brother-in-law’s tavern, Frank’s Place, in downtown Monmouth, Illinois. She was last seen leaving the tavern around 12:20 a.m. on April 9, 1966. When she failed to return home, she was reported missing on April 13. Later that same day, her body was discovered in an empty hog house behind the tavern. She had died from a forceful blow to the abdomen, which ruptured her liver.

Speck was known to frequent Frank’s Place and was questioned by police in connection with Price’s death. He was never charged, and the case remains officially unsolved. The timing, however, is difficult to ignore.

Just months earlier, in 1965, Speck had already murdered Mary Pierce, a Chicago barmaid, strangling her in a crime that drew limited attention and failed to stop him.

Each arrest.

Each release.

Each warning ignored.

The Inevitable Conclusion

None of these acts occurred in isolation. They formed a clear, accelerating pattern—violence escalating in severity, victims growing more vulnerable, and consequences remaining fleeting.

In July 1966, Richard Speck would enter a South Side Chicago townhouse and murder eight student nurses in a single night—an act that horrified the nation and cemented his place in American criminal history.

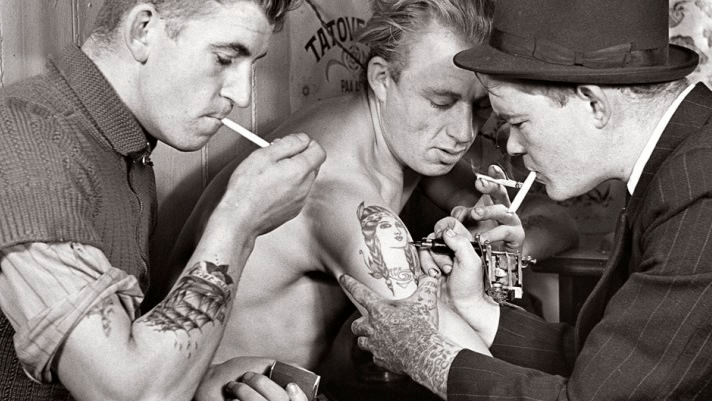

The tattoo came later.

The violence was already in motion.

L.W.

Leave a comment